For over 150 years, it stood as one of the key shipbuilding centers in the United States. During World War II, it earned the nickname “The Fleet Factory” due to its massive output of military vessels. This is the place where the first large battleships were built, where the complex weathered wars and economic downturns, pioneered new technologies, and fostered future reformers. Read on new-york-future.com for more on the dynamic and transformative history of this iconic site.

The Birth of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

In the early 19th century, the land intended for the future Brooklyn Navy Yard was little more than a collection of old docks and swampy plots. The Federal Government purchased the area in the early 1800s, but development stalled for a long time. Political priorities shifted, and the site effectively lay dormant for several years. It wasn’t until the arrival of the first commandant, Jonathan Thorn, in 1806 that the shipyard began to take shape.

The first few decades were relatively quiet: the Commandant’s House, a few workshops, and barracks were constructed, and the territory gradually expanded. During the War of 1812, the Yard became an important base for fleet repair and even a testing ground for early telegraphy experiments.

Shipbuilding accelerated after the war. The first large vessels appeared, including the USS Ohio and Fulton’s ship, the USS Fulton. Between the 1820s and 1830s, the area grew, and a naval hospital was opened on the site.

The Yard often supported the city: its sailors helped fight major fires in the 1830s and 1840s. During this period, Matthew Perry served here—the future naval reformer who founded the Naval Lyceum, oversaw the construction of the first steam-powered warship, and briefly headed the Yard.

Working conditions were harsh: laborers worked 12 to 14 hours a day. It took until the 1840s for them to successfully campaign for a reduction to a ten-hour workday. The real breakthrough came after the decision to create a master development plan. Engineer Loammi Baldwin proposed a well-thought-out street structure and the first large dry dock. Its construction transformed the marshland into a formidable industrial platform.

Becoming a Leading Center of American Shipbuilding

By 1860, Brooklyn had become one of the largest cities in the U.S., and the Yard had transformed into a premier shipbuilding center, employing thousands of European immigrants. At the start of the Civil War, it had 3,700 workers; by 1863, nearly 4,000; and by 1865, the number had soared to 6,200.

During the war, the Yard built 14 large vessels and modernized over 400 commercial ships for the Union blockade of the Confederacy. Work went on around the clock. The first ship specifically built for the war was the screw sloop USS Oneida (1861), which fought in key battles. Due to its strategic importance, the Yard became a target for Confederate sympathizers, but a plot to set fire to the warehouses was quickly thwarted.

After 1865, the number of employees sharply decreased. Wooden shipbuilding technology was becoming obsolete. In 1876, the USS Trenton was the last wooden sailing ship built in Brooklyn.

By 1872, 1,200 people worked at the Yard, and legislation for the first time granted them legal protection and an eight-hour workday. In the late 19th century, with the revival of the naval program, shipbuilding picked up again: ironclads, torpedo boats, and submarines were being built, and the old wooden shipways were replaced with stone ones.

The 1880s and 1890s saw the addition of new dry docks and engineering workshops. Among the most notable ships of the period were the armored battleship USS Maine (1888–1895) and the cruiser USS Cincinnati(1894).

The massive demand for flags, pennants, and powder bags opened the door for women to work at the Yard. By the late 1890s, most flag makers were women, often including the widows of fallen soldiers.

The Era of Greatest Glory

After Brooklyn became part of New York City in 1898, the area developed rapidly: new bridges and subways were built, and the Yard found itself at the heart of the transit network. This made it an appealing workplace for thousands, including immigrants. Despite periodic proposals to relocate or close the Yard, it survived and received a new boost in growth.

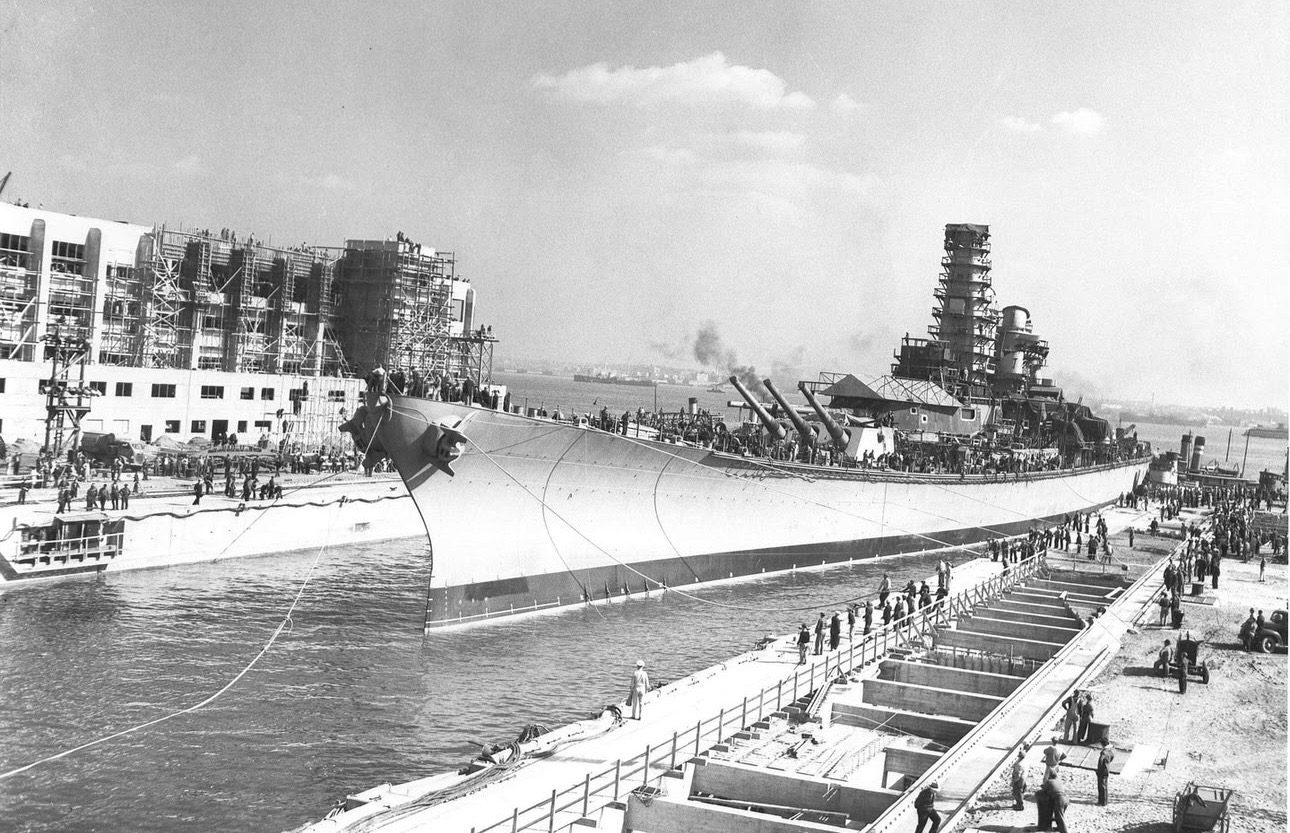

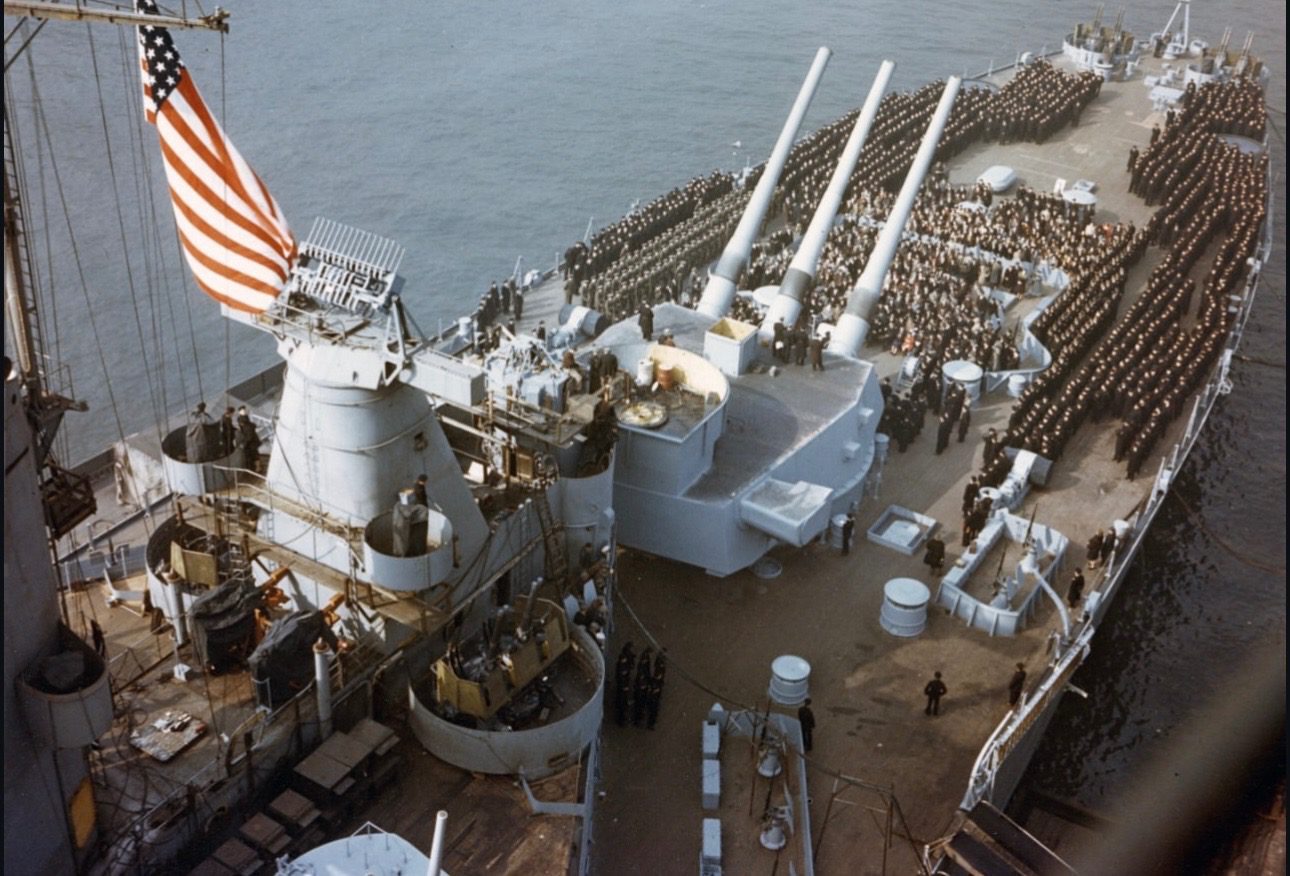

In the early 20th century, the U.S. Navy actively modernized, and Brooklyn Navy Yard became the key site for building large battleships. To accommodate this, the area was expanded, and new docks and workshops were erected. By World War I, the Yard had transformed into one of the Navy’s main production hubs.

During the war, the workforce sharply increased, new facilities and security systems were put in place, and the Yard specialized in the rapid construction of smaller warships. After the war’s conclusion, activity slowed: several large projects were halted by international treaties, and economic crises led to cutbacks.

The situation changed in the 1930s, when rising global tensions spurred a renewed focus on active shipbuilding. The site was renovated, equipment modernized, and the number of employees once again exceeded tens of thousands.

Leading up to World War II, the Yard underwent a massive transformation: it grew significantly larger, acquired new docks, colossal production halls, and updated infrastructure. During the war years, work never stopped. Employee numbers swelled to record highs, and the Yard earned the nickname “Can-Do” for its ability to handle extraordinary workloads.

Closure and Transformation of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

In the mid-1960s, the Federal Government made the decision to close the Brooklyn Navy Yard as part of a large-scale reduction of military facilities. Despite protests and political support, the shipyard officially ceased operations. The last ship was launched mid-decade, and the closing ceremony followed shortly after. This was a major blow to the neighborhood, as thousands of civilians lost their jobs.

After the closure was announced, there were attempts to adapt the site for new uses—proposals included a commercial shipyard, a factory, and even a federal prison—but none materialized. Eventually, the federal government agreed to fund the creation of an industrial park, and the city purchased the territory in the late 1960s, paying a significant sum.

The management of the new complex was entrusted to an organization called CLICK, which promised to bring tens of thousands of jobs back to the Yard. Instead, it became bogged down in conflicts, financial woes, and accusations of a lack of transparency. The first tenants arrived, but development progressed much slower than projected. Ultimately, in the early 1980s, the city replaced CLICK with a new management structure.

Periodically, large companies came to the Yard. First, it was Seatrain Shipbuilding—it grew quickly, building giant tankers, but did not survive the economic turmoil of the 1970s. Then, Coastal Dry Dock became the largest tenant, also ceasing operations due to financial difficulties. By the end of the 1980s, the number of jobs had decreased to a few thousand.

However, it was during this time that the Navy Yard began to change. The decline of shipbuilding opened the door for small and medium-sized businesses. The area became attractive due to affordable space and its proximity to Manhattan. By the early 1990s, many companies were operating there.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard in the 21st Century

The true turnaround began around the mid-2000s. The city invested amounts not seen since World War IIand planned further expansion of the territory.

In the early 2010s, the most ambitious revitalization program kicked off: modernization of production buildings, restoration of some historic structures, and the opening of the BLDG 92 museum. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was transforming into a powerful center for small and medium manufacturing: hundreds of companies operated there, the city’s largest rooftop farm emerged, and Steiner Studios became one of the country’s leading film production hubs.

In the second half of the decade, new large buildings were opened, including the Dock 72 office complex and the updated Building 77. A Wegmans supermarket opened nearby, and the district received a new visual identity.

Concurrently, an updated master plan was prepared: expansion of the territory by millions of square feet, the creation of thousands of new jobs, the emergence of vertical manufacturing buildings, and better integration of the Yard with the surrounding urban environment.

Development continued into the 2020s: In 2023, Pratt Institute opened the first phase of the Research Yard. In 2025, the competition for the second phase of the complex began. The same year, the Yard received $28.7 million from FEMA for recovery from damage caused by Hurricane Sandy.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard is not just about the Navy; it’s about the city’s ability to change with the times. The Brooklyn Navy Yard has proven that even a space created for war can become a place for creativity, industry, science, and community.