He left behind more than just hundreds of patents and dozens of companies. Elmer Sperry translated the principles of stability, precision, and self-regulation into the world of machines. His ideas became the foundation for 20th-century marine navigation, automatic aircraft control, and inertial systems in rockets and spacecraft. Read on new-york-future.com for more about this distinguished innovator.

The Inventor’s Early Years

Elmer Ambrose Sperry was born in the fall of 1860 in the quiet town of Cincinnatus near Cortland (New York State). His birth was a tragic event for the family. His mother died the next day, and the infant was taken in by his aunt and his grandparents—devout Baptists who raised the boy in an atmosphere of discipline and moral principles.

From childhood, the boy displayed a natural aptitude for mechanics. In high school, he excelled in science and drew technical diagrams with exceptional precision—a skill that would later help him explain and disseminate his ideas. The young man spent hours in the technical library of the local YMCA, where he discovered the world of engineering. A trip to the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 was a true revelation for Elmer. The machines, new technologies, and bold inventions all impressed young Sperry and spurred him toward a great ambition.

First Inventions

As a nineteen-year-old, Sperry created his first serious invention—an electric regulator for arc lighting. With support from the Cortland Wagon Company, he gained access to the tools, engineers, and legal help needed to transform his idea into a complete lighting system.

Moving to Chicago and relying on investments from fellow townspeople and the Baptist community, Elmer began selling his own arc lighting system. Despite the technical quality, his competitors proved stronger, and Sperry’s company went bankrupt after five years.

But this failure became one of the most valuable experiences of his life. It was then that Elmer delved deeply into automatic control and feedback systems—topics that would later help him create his famous stabilizers and compasses.

In 1887, Sperry developed a bold engineering solution for coal mines—an electrical power system with specially heated copper wires protected from corrosion. This made it possible to lower custom-built electrical equipment deep underground, where engineers had previously never imagined electricity. Coal extraction sharply increased, and Sperry founded the Sperry Electric Machinery Company in 1888, turning mining needs into a business advantage.

Not stopping at mines, Sperry created the Sperry Electric Railway Company in 1890.

Using developments born in the mining sector, he adapted electric motors for city streetcars in the challenging, hilly cities of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Concurrently, Elmer experimented with the transportation of the future—electric cars. Work on them led to a series of patents that later became the basis for the development of portable lead-acid batteries.

In 1896, Sperry took a daring step: he drove his own electric car to Paris. It was the first American-made automobile to appear on the streets of the French capital—a small victory that technical magazines later wrote about. In 1894, his railway company, along with its patents, attracted the attention of the giant General Electric, and Sperry sold his developments to move on.

At the turn of the century, in 1900, Elmer founded an electrochemical laboratory in Washington, D.C. Together with chemist Clifton Townshend, they created processes for manufacturing high-purity caustic soda and recovering tin from scrap metal—inventions that quickly found industrial application.

Elmer Sperry moved from one idea to the next, as if testing the world’s resilience, looking for the field where his talents would fully flourish. Each step was a link in the long chain that would ultimately lead him to create inventions that changed seafaring and aviation forever.

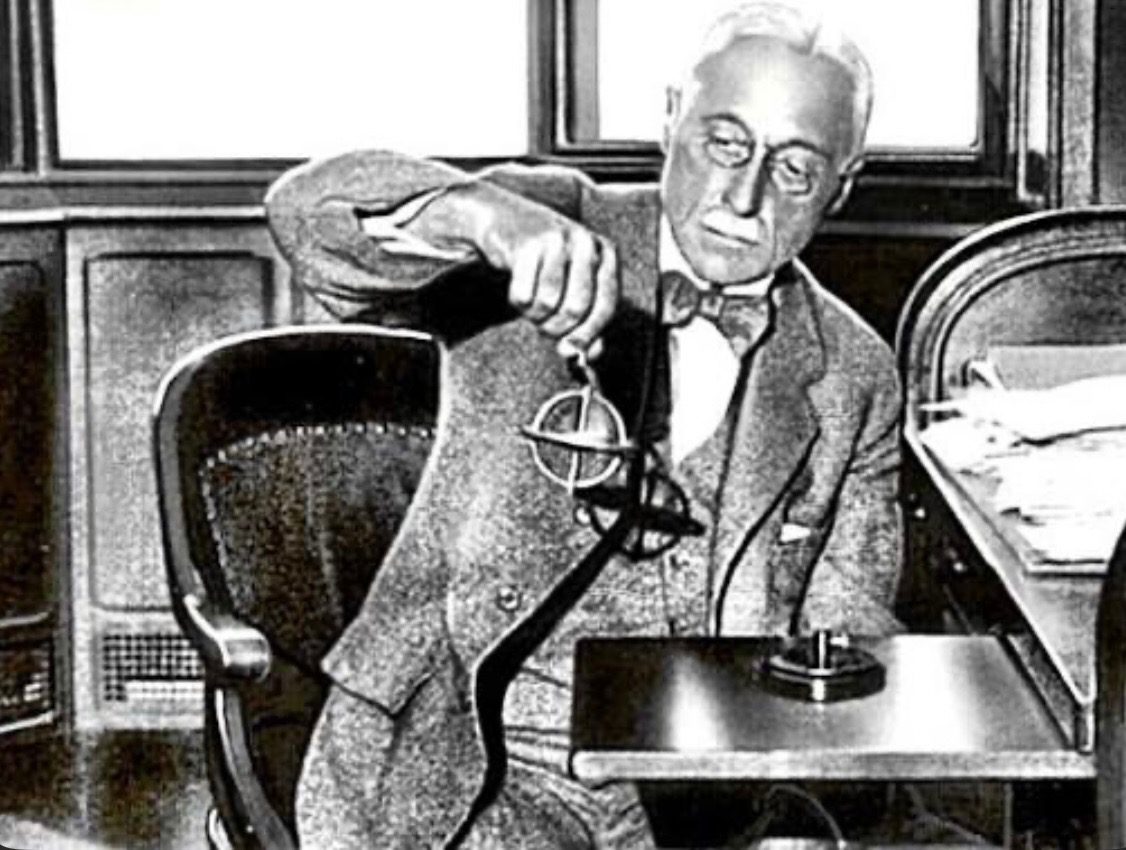

The Man Who Tamed Motion

In 1898, Sperry took a transatlantic voyage and experienced firsthand the effect of a prolonged ship roll. New steel steamships would swing almost like pendulums, and even seasoned sailors suffered from the rocking.

Sperry, instead of complaining, came up with a solution: installing a massive gyroscope inside the hull to counteract the roll. But instead of passive systems that merely waited for the ship to tilt, Sperry created an active stabilizer:

- a sensitive gyroscope to detect the start of a wave;

- servo-motors that instantly engaged the main gyroscope;

- an automatic control and feedback system.

This was a genuine breakthrough—the ship gained a “premonition” of the wave and reacted before it hit.

In 1911, the first stabilizers were installed on U.S. Navy ships. They worked excellently, although their high cost prevented mass implementation.

Sperry founded the Sperry Gyroscope Company in Brooklyn. Soon, gyrocompasses were being installed on American, British, French, Italian, and Russian warships. During World War I, the gyrocompass even controlled a ship’s rudder, holding a perfect automatic course.

The Navy’s needs forced Sperry to create increasingly complex stabilization systems. The U.S. Navy supported his work with personnel, materials, and funding—a collaboration that replaced the private investors he had previously relied on.

The Aviation Revolutionary

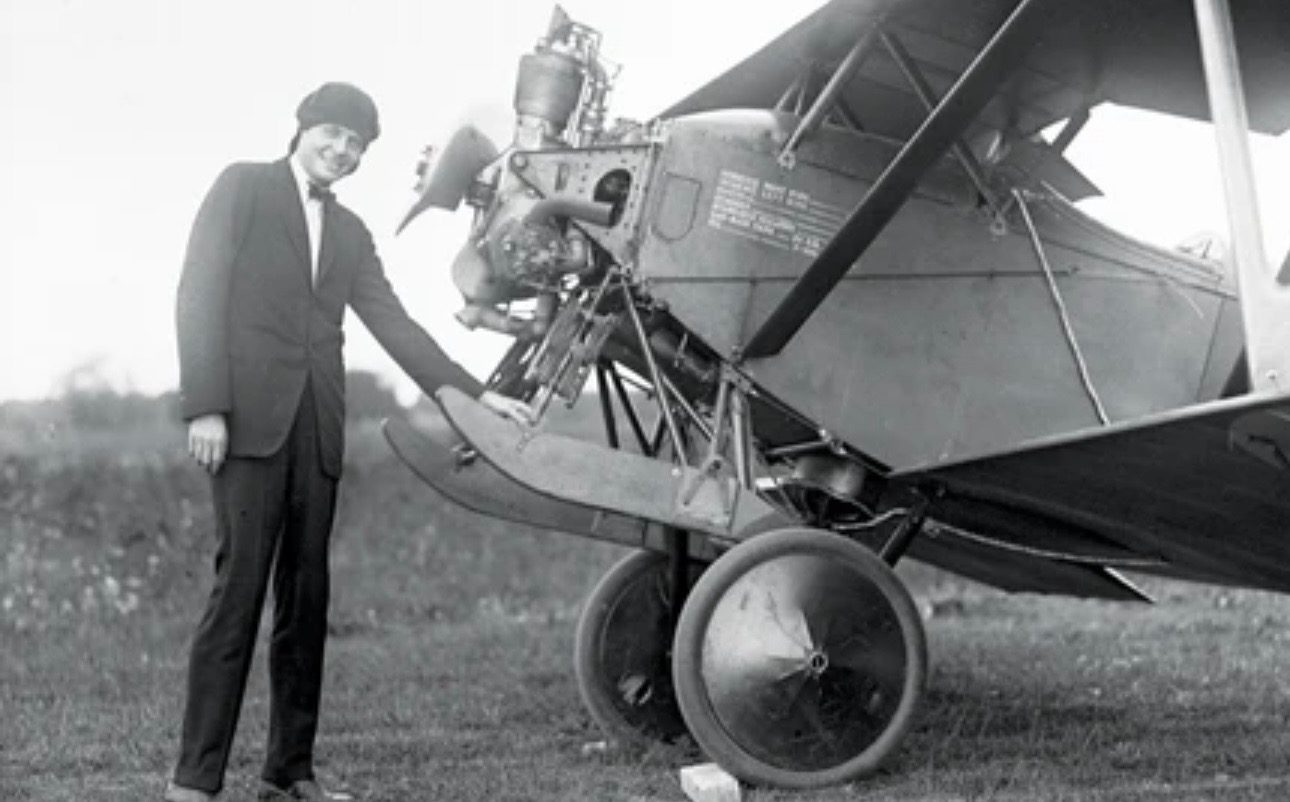

In the early 1910s, Elmer Sperry decided to take on what others considered impossible: to make an airplane smarter than its pilot.

Working alongside his son, Lawrence Sperry, he created a gyroscopic system capable of automatically controlling the ailerons and elevators via servo-mechanisms. The technology, which previously only massive ships could handle, Sperry successfully “put on wings.”

At the Aero Club of France competition, Lawrence demonstrated the stabilizer by flying past the judges without touching the controls once. This triumph earned Sperry the Franklin Institute Medal and cemented his reputation as an innovator.

Although the system never became mass-produced, it became the foundation for the future autopilot that his son would develop.

Together with inventor Peter Hewitt, Sperry created the Hewitt–Sperry automatic airplane—one of the earliest predecessors of modern UAVs.

The problem of the magnetic compass “tumbling” during turns led Sperry to invent the gyroscopic turn indicator. This later became the basis for the now-familiar turn and slip indicator. By adding a directional gyro and a gyro horizon to it, Sperry essentially created the set of basic flight instruments without which no aircraft takes off today.

Wartime demand made Sperry’s gyroscopes key components in torpedoes, ships, aircraft, and even early spacecraft. The company expanded to include fire-control systems, bomb sights, radar, and even automation for takeoff and landing.

During World War I, Sperry worked on a “flying bomb.” In March 1918, he conducted an experiment: controlling an aerial torpedo over half a mile using a radio signal—which seemed like science fiction at the time.

Elmer Sperry’s Final Years

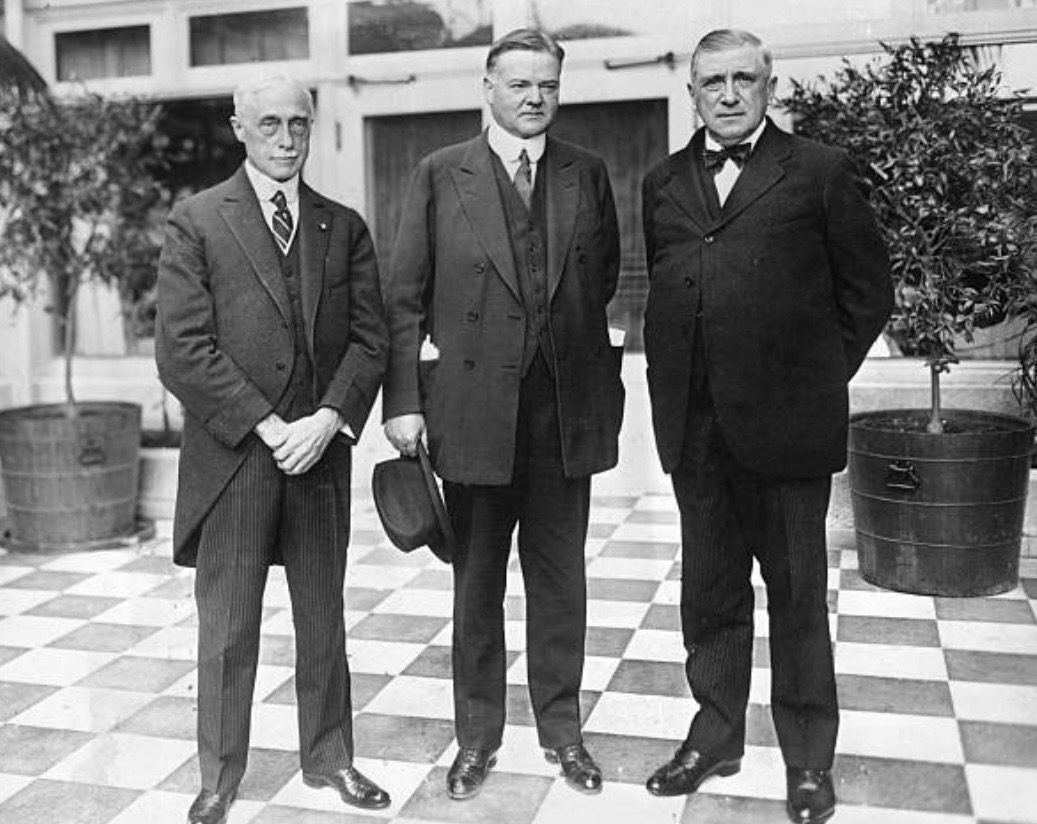

By the end of World War I, Elmer Sperry’s name was known not only by engineers and sailors but by the general public. The inventions he created in the solitude of his laboratories suddenly became part of the global conflict—British, Russian, German, and American navies relied on his gyroscopes. He became the second most recognized figure in the world of invention after Thomas Edison himself.

Sperry served on the Naval Consulting Board, headed important projects, received international awards, and founded professional institutions and societies. His influence on American technical science was so profound that he co-founded both the AIEE and the American Electrochemical Society—organizations that shaped 20th-century engineering education.

But with fame came blows. In 1923, his son Lawrence died—the same young man who had once made the famous “hands-off” flight. The custom-designed aircraft crashed into the English Channel. Seven years later, fate prepared another trial: his wife, with whom the inventor had spent his entire life, died in 1930. That same year, after surgery to remove gallstones, his body succumbed to complications and overwhelming grief. On June 16, 1930, at St. John’s Hospital in Brooklyn, Elmer Sperry passed away. He was 69 years old.

Until his last days, he remained a person invited to meetings with presidents and ambassadors. The Elmer A. Sperry Award, granted for technological breakthroughs in transportation, was later established in his honor. A ship, the USS Sperry, and a building at SUNY Cortland were also dedicated to him.

In his lifetime, Elmer Sperry founded 8 companies and received over 400 patents. Just a few years after his death, the Sperry Gyroscope Company evolved into the Sperry Corporation—one of the technological giants of the mid-20th century, which later merged into Unisys.