Even after nearly a century, the Whitney Museum is still synonymous with “contemporary.” This vision has guided the institution since its founding and continues to shape its identity today. The museum, a true source of pride for New York City, is a powerful showcase of American art. Yet, behind its celebrated façade lies a rich history of struggle and determination. To truly appreciate the Whitney Museum’s journey, one must delve deeper into its origins, its path to success, and the extraordinary people who built this cultural icon. Read more at new-york-future.

A Museum Born of Revolution

At first glance, the Whitney Museum might seem like any other esteemed institution, celebrated for its history, achievements, and collections. But in reality, the museum ignited a revolution in the art world. While the global art scene was fixated on ancient works and recognized only European masters, the Whitney turned its attention to American artists working right here, right now. Defying a chorus of critics who dismissed new works as valueless, the museum’s founders championed their own bold vision. This pioneering spirit belonged to two remarkable women: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Juliana R. Force. In 1931, they opened a museum dedicated exclusively to American art and artists. The founders understood that America was a country built on modernity and fresh ideas—and that “new” didn’t mean “bad.” Their institution became an embodiment of their country’s cultural essence.

It all began with a rejection. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney had amassed a huge collection of American art, a testament to her belief in new talent. She had collected over 600 works and, to prevent them from languishing in storage, decided to donate the entire collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Whitney even offered a large sum of money to help the Met build a wing to house the works. However, the Met’s director spurned her generous offer, belittling the value of her collection. That moment was the catalyst: Whitney and Force resolved to create their own institution to promote American artists and their work. The Whitney Museum debuted to the public in November 1931. While Juliana Force served as the first director, Gertrude Whitney’s contribution was immense. She financed the museum, donated her own art, and served as its driving force and organizational inspiration.

While the Whitney Museum’s creation was a labor of love for its founders, it also faced significant challenges. The project had a strong foundation, as both Gertrude and Juliana were deeply connected to the art world. Whitney was an artist herself and a patron of others, while Force was her indispensable right hand. The women had extensive experience organizing exhibitions, and the museum was a natural next step for them. However, they chose a path that was far from typical, one that championed contemporary, lesser-known American artists. The founders made it clear that they would feature the work of living artists and introduce new names to New Yorkers. This radical approach clashed with an art community that was heavily focused on European standards. The Whitney was not seen as an equal by its peers. But while the critics were busy critiquing, the public wholeheartedly embraced the new museum.

Milestones in History

The Whitney Museum’s story began with the inspiring words of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. She shared her hopes and aspirations with her guests—simple yet profoundly important goals. She believed in the creative talent of her country and was determined to share its riches with the public. To her, the museum’s true success would be measured by the joy each visitor found in its collections.

The museum’s first home was on West 8th Street, a stone’s throw from Gertrude’s personal studio and the heart of New York’s art scene. Despite its large collection, the team knew that the public craved new names. Just one year after opening, the museum launched the Whitney Annual. This yearly event, held from 1932 onward, became a mecca for talented artists, offering unknown creators a chance to be seen. The museum eagerly acquired the best works, adding them to its collections. In 1973, the event got its now-iconic name: the Whitney Biennial. The team uncovered true gems of American art and unlocked its potential, expanding the event to include painting, sculpture, photography, and various performance art forms.

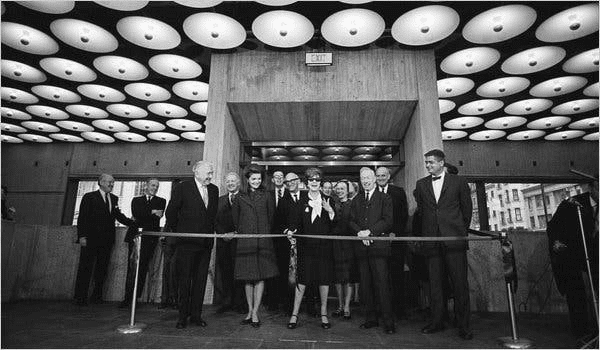

Another major milestone was the Whitney Museum’s move to a new building in 1966. The institution enlisted the expertise of Marcel Breuer, who designed a home that drew even more attention to the museum. No one could ignore his striking design. The building was called everything from gloomy and cumbersome to unusual and flawless, but it left a lasting impression on everyone who saw it. The Whitney remained there until 2015, when it moved again.

With ever-growing collections, plans, and ambitions, the museum needed more space. In 2010, the Whitney began construction on a new building that would usher in a new era. Architect Renzo Piano masterfully executed the design. This time, the new building was met with widespread praise and admiration. And it’s no wonder—the new home impressed with its vast open spaces, creative design, effective zoning, and terraces. The move finally solidified the Whitney Museum’s place as a major player in the art world. The museum team, with ample resources and space, calmly continued to pursue its vision. Guests can visit the exhibition halls, enjoy open-air performances, and explore the library or restaurant. And the museum ensures that the artistic part of their leisure is well-cared for.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: The Trailblazer

A central figure in the Whitney Museum’s story was Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney—a talented and unconventional personality. Born and raised in New York City, she dedicated her many talents to her hometown. Though she came from one of America’s wealthiest families, she was a true outlier among the elite, which proved to be a major advantage for the American art world. With private lessons, exclusive schools, and extensive travel, she led the life of a young socialite. Yet, amid a meticulously planned schedule, she always found time to visit museums, cultivate her passion for art, and dream of a different future.

Gertrude debuted in society in 1895 and married Henry Payne Whitney a year later. Neither her husband, her family, nor her social circle understood her desire to pursue a creative career. However, she was smart and resourceful enough to use her position to her advantage rather than complain about it. Despite the widespread disapproval, Gertrude ignored the obstacles and forged her own path as a sculptor.

Whitney studied under artists like Andersen, Fraser, and O’Connor, attended the Art Students League of New York, and traveled through Europe to gain experience in different art circles. She had the courage to create her own works and enter competitions. She won grants, exhibited her creations, took commissions, and left behind a significant legacy. Her most famous works include the Titanic Memorial, the Aztec Fountain, and the Washington Heights-Inwood War Memorial.

Beyond her own art, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was a dedicated patron of others. She provided financial assistance to countless artists, sponsored their careers, purchased their paintings, and introduced them to the public. Many of her contributions remained anonymous, but she was instrumental in the development of both talented artists and established institutions. She even created a space near her home and studio where American artists could create, hold meetings, and present their work. The project was a massive success, and when it outgrew all expectations, a new institution was born: the Whitney Museum, which became perhaps Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s greatest achievement.

The Museum’s Guiding Principles

The Whitney Museum was ahead of its time from its very first year, introducing new ideas and values that have endured for decades. This is why the institution is still seen as a modern and welcoming place. So what are the principles that guide the museum?

First and foremost, the museum’s very origin and concept speak to its most fundamental principle: the development and promotion of American art. As early as the 1930s, the founders recognized the bias against artists from the United States. While everyone else was focused on European examples, the Whitney declared that its galleries were for living and talented Americans. The museum helped launch the careers of many famous artists and created opportunities for them to thrive in the here and now. The institution continues to follow this path today.

Equally important is the Whitney Museum’s unwavering support for those whom others refuse to understand. The team fought for the right of women to exhibit their work, invited African American artists, created a welcoming space for artists of all backgrounds, and brought together different parts of the United States. The museum isn’t afraid to expand its horizons—and it does so successfully. What’s more, the team champions an inclusive idea of America and looks after artists during critical moments in their careers. The Whitney also works with artists who are just starting out, offering invaluable support to those who need it most.

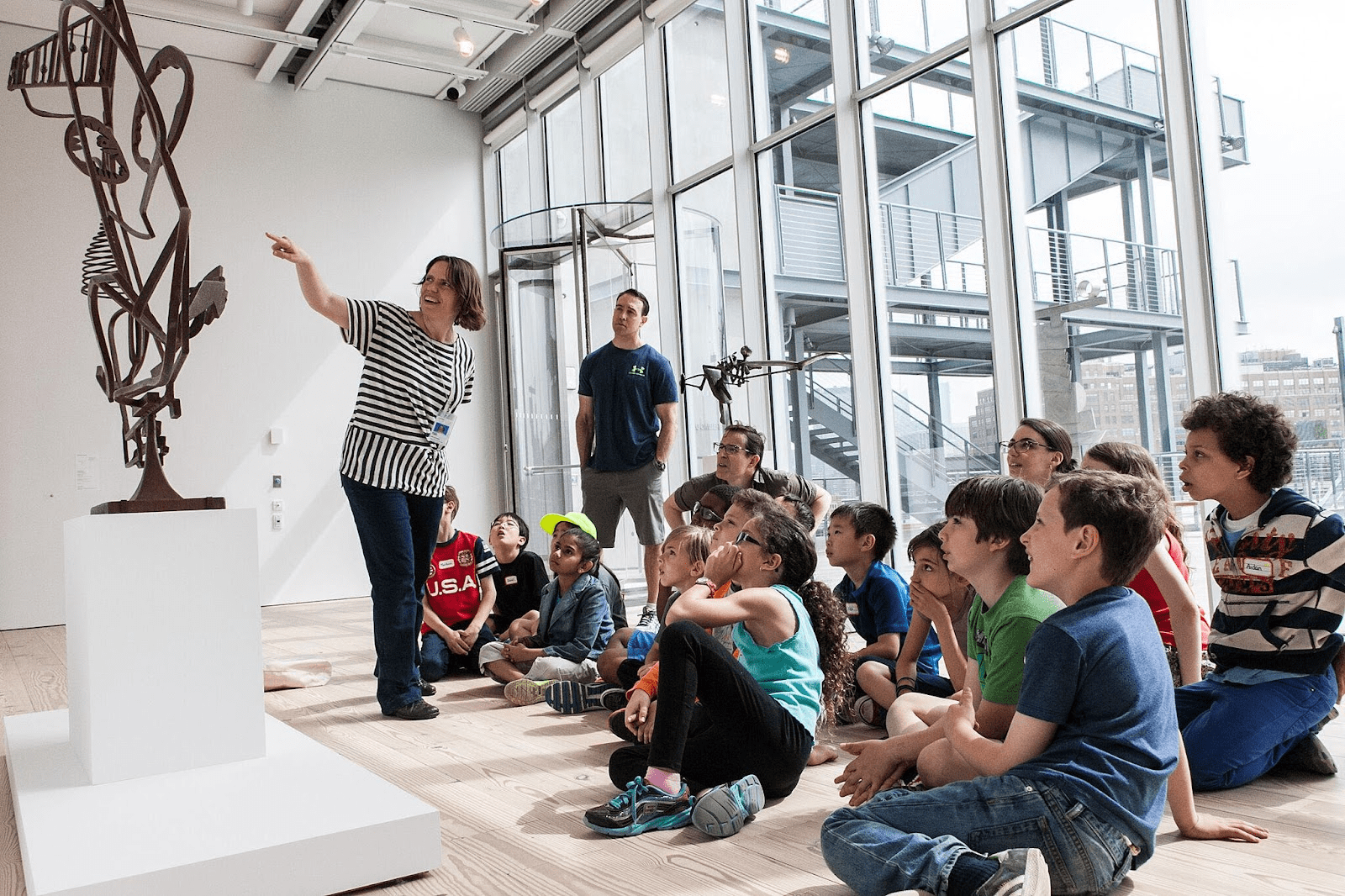

Another key principle is the museum’s engagement with other institutions. You can find countless programs for schools, universities, colleges, and other organizations in New York City. The Whitney Museum organizes film screenings, symposiums, lectures, courses, tours, and other events. The team offers engaging activities for families, people with visual or hearing impairments, and private access programs, among others. The institution lives in sync with the rhythm of the city, supporting and encouraging new ideas. For over 50 years, the Whitney Independent Study Program has provided educational opportunities for artists, critics, curators, and other art professionals, ensuring that the museum remains a contemporary place for new generations.