American electrical engineer Edwin Armstrong developed FM radio and was a pivotal figure in the US radio industry. Despite his groundbreaking research, he spent a significant portion of his life in court, battling for the authorship of his inventions. His grueling, exhausting legal fights against major corporations ultimately destroyed Armstrong, yet they couldn’t diminish his monumental contribution to wireless communication. Learn more at new-york-future.

The Future Inventor’s Early Life

Edwin Howard Armstrong was born in New York City on December 18, 1890. He was the eldest son of John and Emily Armstrong. His father worked at the Oxford University Press publishing house, eventually rising to the position of vice president. The family belonged to the middle class and was religious.

At the age of eight, Edwin contracted Sydenham’s chorea, a rare neurological disorder often caused by rheumatic fever. The illness left the boy with a persistent facial tic that worsened under stress. As a result, he was homeschooled for two years, limiting his social interaction with peers.

After the family moved to Yonkers, Edwin became fascinated with the stories of Guglielmo Marconi and Michael Faraday. Inspired, he resolved to become an inventor himself. He was keenly interested in electrical and mechanical devices, had a love for heights, and even constructed a makeshift antenna tower in his backyard. He spent countless hours tinkering in the attic, mastering Morse code and obsessively trying to make its signals louder and transmit them over greater distances.

The Academic World

In 1909, Edwin Armstrong enrolled as a student at Columbia University in New York. His mentor was Professor Michael Pupin, who had invented a method to increase the range of message transmission over communication cables. Pupin was a staunch supporter of Armstrong’s research and often defended him. This was necessary because Armstrong was deeply focused on his scientific work, frequently challenged conventional wisdom, and often debated his professors.

Despite his difficult nature, Armstrong successfully graduated from Columbia University in 1913 with a degree in electrical engineering. During World War I, he served in the Signal Corps, and later became a research assistant to Professor Pupin.

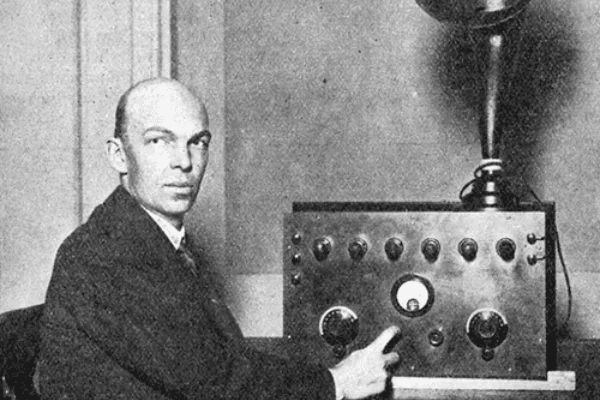

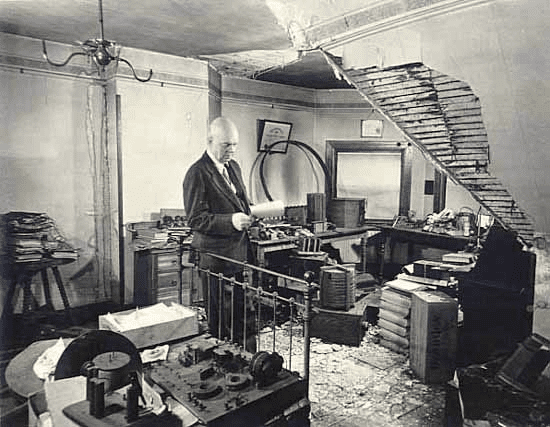

He eventually established his own financially independent research laboratory. He declined his university salary and chose not to teach classes. In 1934, he was appointed Professor of Electrical Engineering, a position he held for the rest of his life.

Inventions and Challenges in Edwin Armstrong’s Life

While still a student, Edwin Armstrong spent years experimenting with vacuum tubes (audions). Lee de Forest invented this device in 1906 but couldn’t fully explain its operating principle. De Forest attempted to use the tubes for radio signal transmission, but the sound was far too faint, audible only through headphones.

After years of studying the audion, Armstrong not only explained its operation but also managed to amplify the signal volume by using positive feedback (regeneration). His subsequent research laid the foundation for the development of continuous-wave radio transmitters.

In 1913, the young scientist prepared demonstrations and scientific papers documenting his research and filed for patent protection for his discoveries. He was granted a US patent in October 1914, marking the beginning of his tribulations.

Initially, Lee de Forest dismissed Armstrong’s findings as insignificant. However, once Armstrong received the patent and the practical importance of his work became obvious, de Forest filed several competing patent applications. De Forest claimed he was the one who discovered the phenomenon of regeneration, citing a corresponding entry in his lab notebook dated 1912.

A protracted legal battle ensued. To cover his costs, Armstrong issued non-transferable licenses for his patent to small radio equipment manufacturers, who in turn paid him royalties on sales. In 1924, the court ruled that Lee de Forest was, in fact, the inventor of regeneration. A shocked Edwin Armstrong appealed the decision, but the ruling was never overturned.

Following this setback, the inventor even attempted to return his Institute of Radio Engineers Medal of Honor. He had received the award in 1917 in recognition of his achievements and publications concerning the audion’s operation. The organization’s board refused Armstrong’s request and stood by him, though this had no bearing on the court’s decision.

Despite these events, the scientist pressed on with his research. His next breakthrough came after World War I: the development of the “superheterodyne” radio receiver circuit. This innovation made radio receivers more selective and sensitive—the way we are accustomed to using them today.

In 1919, Armstrong applied for the patent and received it a year later, only to find himself embroiled in another patent war. This lasted until 1928 and also ended unfavorably for the inventor, yet it yielded one positive outcome. While preparing for the court proceedings, the scientist accidentally discovered the phenomenon of super-regeneration. He sold the patent for this invention to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) for $200,000, becoming a major shareholder in the company.

FM Radio

One of Edwin Armstrong’s most critical discoveries was the introduction of the “wide-band” FM frequency range. Early radio communication was severely hampered by noise from electrical equipment and thunderstorms, yet no one understood how to eliminate it. Armstrong found the solution.

In 1933, he secured five US patents for his FM system, which effectively filtered out this noise. However, when the new system was presented to the president of RCA, he failed to appreciate its potential and denied the scientist further funding and collaboration.

Armstrong then began working with smaller members of the radio industry to promote his invention. Believing that FM had the potential to replace the prevailing AM stations and receivers, he presented the new system to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). His idea was accepted, but it posed a significant challenge to the established radio industry, specifically AM radio giants like RCA, CBS, ABC, and Mutual.

In 1940, RCA sought to buy the FM patents, but Armstrong refused. This refusal spurred a fresh wave of lawsuits that continued even after the inventor’s death.

Personal Life and Death

In 1923, Edwin Armstrong married Marion MacInnis. As a wedding gift, his bride received the world’s first portable superheterodyne radio receiver. She was her husband’s unwavering supporter, and the couple was happy.

Nevertheless, the countless legal battles severely degraded Armstrong’s mental health and financial standing. By the fall of 1953, he was nearing bankruptcy. The couple had only their pension money, which was deposited in Marion’s name. When he asked for a portion of it to continue the lawsuit, his wife refused. Following an argument, she left home to stay with her relatives. They never saw each other again—on the night of February 1, 1954, Armstrong jumped from his Manhattan apartment window and died.

Afterward, Marion continued to manage the legal affairs of his estate and won most of the cases. Thanks to her efforts, Armstrong was officially recognized as the inventor of FM radio. In 1955, she also established the Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation.