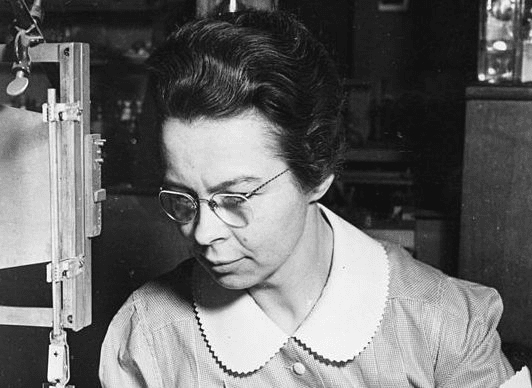

American chemist Katharine Blodgett not only invented groundbreaking “invisible glass” for optical equipment but was also the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in physics from Cambridge University, gaining recognition in the scientific world of her time. She possessed not only the intellect and talent but also the courage to pursue her passion. new-york-future shares more about the life and scientific journey of this New York native.

Family and Early Life

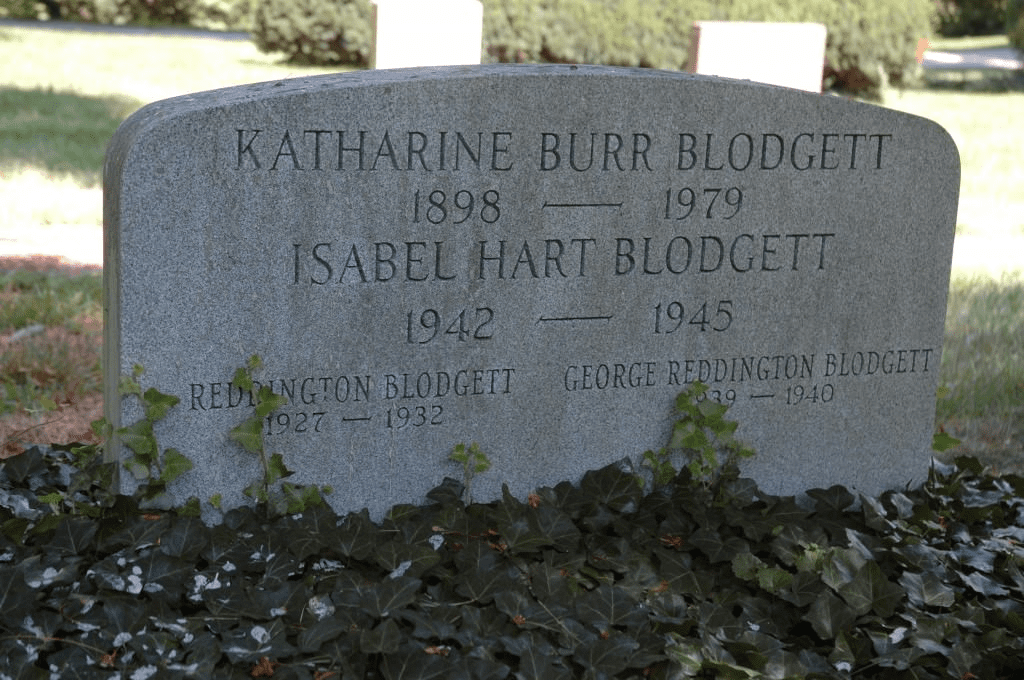

Katharine Blodgett was born in New York City on January 10, 1898. She was the second child of Katharine Buchanan and George Blodgett; she had an older brother. Her father worked at General Electric, where he headed the patent department. Tragedy struck before her birth – he was fatally shot by a burglar. As a result, Katharine was raised by her mother.

In 1901, the Blodgetts moved to France, where the children learned French. They returned to the U.S. a few years later but continued to travel to Europe periodically. Because of this, Katharine did not begin her formal education until she was 8 years old. In 1912, she enrolled at the Rayson School in New York City. After graduating, she went on to study at Bryn Mawr College.

General Electric: Katharine Blodgett’s Education and Scientific Career

Katharine was a curious child with a keen interest in science. During her senior year of college, she visited General Electric. The renowned chemist Irving Langmuir, a former colleague of her father’s, gave her a tour of the laboratories. After discussing her interests, Langmuir offered her a research position, but on the condition that she first obtain a higher education.

At that time, in the early 20th century, the fields of science and education were still largely closed to women. Male scientists often did not take them seriously or provide opportunities for advancement. However, Langmuir recognized Blodgett’s talent and convinced her to pursue further studies.

In 1918, Katharine earned her master’s degree from the University of Chicago, where she developed an application for carbon filters in gas masks. Her thesis advisor was Harvey B. Lemon. This work earned Blodgett her first recognition and a position as an assistant in Langmuir’s laboratory. At the time, the future Nobel laureate in chemistry was working on creating monomolecular films and involved Blodgett in his research. Moreover, he encouraged his capable assistant to continue her education and helped her gain admission to Cambridge University.

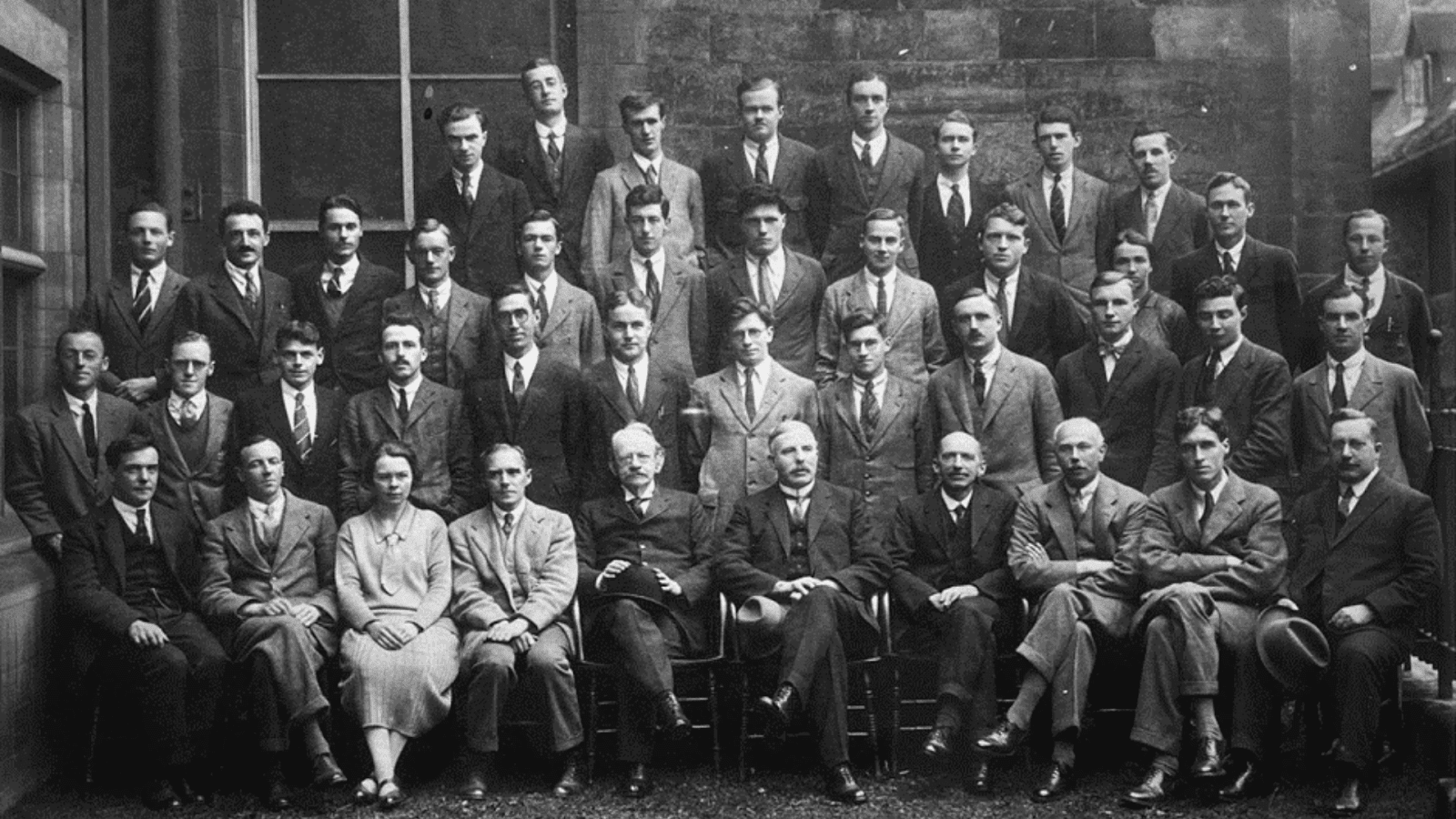

In 1924, Katharine joined the laboratory of the famous physicist Ernest Rutherford and completed her dissertation on the behavior of electrons in mercury vapor. Her work was highly praised during her defense, and Blodgett became the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in physics from Cambridge. Upon returning to the U.S. in 1926, she resumed her collaboration with Langmuir.

Katharine Blodgett’s “Invisible Glass”

While working at General Electric, Blodgett made many discoveries. For instance, during World War II, she worked on smoke screen technology that improved the efficiency of oil evaporation. But her most significant mark on science and technology was her invention known as “invisible glass,” which was a multilayer anti-reflective coating for glass.

Irving Langmuir had previously developed a process for creating atomic-level layers, and Blodgett expanded and perfected this technique. This allowed for the application of multiple layers of coating onto glass, making it completely transparent—or invisible. This groundbreaking development helped eliminate the distortion caused by light reflecting off the glass in optical equipment. It became a true revolution for eyeglasses and microscopes and is still used in manufacturing today.

The scientist received a patent for her development in the spring of 1938. The following year, an article detailing the development was published in the journal “Physical Review.” It caused a great sensation. Popular publications like “Time,” “Life,” and “The New York Times” even wrote about “invisible glass” and its inventor.

Blodgett’s invention played a crucial role during World War II, as it was used in aircraft cameras and submarine periscopes. Additionally, the film industry took an interest in “invisible glass.” It was used, for example, during the filming of the famous movie “Gone with the Wind,” which is known for its crystal-clear cinematography.

Later, other research groups made these coatings more durable, and they gained widespread commercial use in the production of eyeglasses, camera lenses, microscopes, car windshields, televisions, and computer screens.

As for Blodgett herself, she went on to work on creating absorbents for poison gases, developed a method for de-icing aircraft wings, and improved smoke screens. She created a “color gauge” to measure the thickness of coatings and researched electrically conductive glass. She retired from General Electric in 1963.

Awards and Recognition

Throughout her life, Katharine Blodgett gained fame and recognition. She received honorary doctorates from Elmira College, Western College, Brown University, and Russell Sage College. In 1943, she earned a star in the “American Men of Science” publication, recognizing her as one of the thousand most distinguished scientists in the U.S. Additionally:

- She was awarded the Francis Garvan Medal by the American Chemical Society (1951).

- She was chosen by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce as one of 15 “outstanding women” in 1951.

- She was honored as a scientist by the First Assembly of American Women.

The scientific community continues to honor her memory. In 2007, Katharine Blodgett was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

The Famous Scientist’s Personal Life

Katharine Blodgett spent most of her life in New York. She bought a house across the street from where she was born and lived there. The scientist was active in a local theater group and actively participated in civic and charitable organizations. She served as the treasurer for the Traveler’s Aid Society.

In the summer, she enjoyed vacationing at Lake George in upstate New York. She was passionate about gardening and astronomy, collected antiques, and even wrote poetry.

As for her personal life, she never married or had children. She preferred a “Boston marriage,” which meant cohabiting with female friends without romantic involvement. For a long time, she lived with Gertrude Brown, and later with Elsie Errington, a woman from England. This arrangement freed the scientist from many domestic duties, except for cooking her favorite dishes. Blodgett herself never commented on her personal life and left no records on the subject.

The famous scientist’s niece and namesake, Katharine Blodgett Gebbie, became an astrophysicist and civil servant. In her autobiography, she described her aunt’s visits to her family. Her aunt would always arrive with large suitcases full of various equipment and perform “magic,” which consisted of small science experiments with colors and films. This had a significant influence on her niece’s decision to pursue a scientific career.

Katharine Blodgett died on October 12, 1979, at the age of 81 in her own home. Her contribution to the advancement of science remains important and valuable, not only for her inventions but also for her courage and determination to work alongside men. Throughout her life, she accomplished what was considered impossible for a woman of her time and became a role model for hundreds and thousands of girls passionate about science.